Part 2: The Math Behind the Go/Stay Decision

With a solid framework in hand, players are just an hour's worth of middle school-level math away from having a clear sense of which path they should choose

This week’s article is heavy on math, but none of it is particularly complicated. The hard part is setting up the analysis framework, which I explained in last week’s article. I have no idea how many players use such a structure for analyzing their options, but even if not explicitly, these are the general variables one must consider, and this article will shed light on how that process can play out, as well as how NIL changes the math. If you missed Part 1 in the series, I suggest going back and reading it before continuing on.

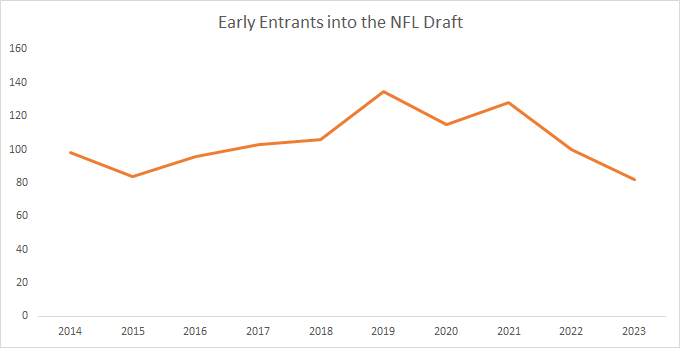

Early data suggest that NIL is associated with less players declaring for the draft early.

While that may be true in the aggregate, each decision is unique. However, the framework I employ below would, I suspect, cover about 90% of the considerations most players weigh before making their decision on whether or not to declare early for the NFL Draft.

To see how that decision process might play out, in addition to illuminating the precise role NIL now plays, I will present two Virginia Tech case studies. The first is for Darren Evans, who declared for the 2011 draft, while the second is a hypothetical for Bhayshul Tuten who, at this point, appears the most likely candidate for early entry.

Case Studies

Out of all the positions on the field, running backs face some of the greatest wear and tear. From a starring position 20 years ago to more of a plug-and-play deal now, value has dropped for those who carry the ball for a living. To understand the role NIL is playing in decisions to go pro early, I thought it would be helpful to go through two case studies. One (Darren Evans) is real, and one (Bhayshul Tuten) is hypothetical, though based on real information.

DARREN EVANS

Running Back, Declared for the 2011 NFL Draft following his R-JR season

Darren Evans elected to forego his final year of eligibility to enter the 2011 NFL Draft after leading the ACC Champion 2010 squad in rushing. He told reporters he expected to be drafted in the third or fourth round, but he went undrafted. Evans signed with the Colts as an undrafted free agent and hung around with the team for a season, seeing little action. Evans played in only three games as a pro.

Decision Analysis

Regardless of what Evans had been told, he was always, realistically, just a late round option. In terms of quantitative factors, Evans, at best, was looking at a moderate signing bonus with nothing else guaranteed. He was an out-of-state kid, so the value of his scholarship was high, but he was on-pace to graduate in the spring of 2011, so taking some graduate classes for a semester didn’t offer much additional value. Injuries were certainly a concern, as he missed the entire 2008 season with a knee injury. Injury insurance was available at the time, but it was generally of the Loss of Value (LOV) variety back then, so it could not be counted on to the extent that it can be now. When he announced, Evans had not signed with an agent, and it is uncertain to what extent he was aware of the financial commitment required.

On the qualitative side, Evans’s considerations were as follows:

Injury Risk: High (missed 2008 with a knee injury)

Legacy: Low (he held the single game rushing record, but was not in line to secure any other major record)

Family: High (he was a married father of a young child)

Brotherhood: Low (no special connection to his recruiting class, 2010 was the seventh straight 10-win season)

Brand: Low (no off-field issues, his image was fine)

Love for the University and College Life: Low (he wanted to make money to support his family)

Had NIL existed in 2011, Evans would have likely returned for his R-SR season. The Hokies were expected to be good again in 2011 and, while he could expect to share carries with David Wilson, that would mean less wear and tear on his body. In that case, Virginia Tech would have returned one of the best backfields in the nation, and media attention would have been high.

The 2011 offensive line featured four seniors, and Jarrett Boykin and Danny Coale were the starters out wide, so one could reasonably expect a lot of running lanes. Ultimately, Evans wanted to support his family, and a decent NIL deal would have likely sufficed, given the uncertainty around his draft status and potential to improve it.

Bhayshul Tuten

Running Back, JR in 2023

Bhayshul Tuten transferred to Virginia Tech after rushing for 1,363 yards at North Carolina A&T in 2022. Like Evans, who was coming back from a major injury in 2010, Tuten enters the 2023 season as a bit of an unknown. Hokie fans didn’t even see much of him at the spring game, which was dominated by Bryce Duke and Chance Black.

At 5’11”, 200 lbs., Tuten is a bit on the small side for an every down back in the NFL, but if he can match last year’s rushing total at the P5 level, he will certainly draw the attention of draft scouts as a possible Day 3 selection.

Decision Analysis

Tuten has not had a major injury in college, but injuries are always a concern for running backs, especially small ones. Unlike Evans, Tuten would have access to a Critical Injury (CI) rider on a potential Permanent Disability insurance policy, so if he were to return to Virginia Tech for his senior season, his financial picture would be much clearer in the event of a serious injury.

Tuten is from New Jersey, so his (out-of-state) scholarship holds significant value. In addition, as a transfer entering his third academic year, it is unlikely that Tuten would be able to earn his Bachelor’s degree by the end of the 2023-24 academic year, especially considering that declaring early would likely mean foregoing classes during the spring semester.

Finally, given the larger football staff in 2023, and potential counseling through Triumph NIL, one can safely assume that Tuten will be well versed in the cost side of hiring an agent, tax considerations, etc.

On the qualitative side, Tuten’s considerations are as follows:

Injury Risk: Medium (solely position-based)

Legacy: Low (it is unlikely he will contend for any major VT record or accolade above an All-ACC team)

Family: Low (nothing public, although this could always change)

Brotherhood: Low (as a transfer, he does not have a connection with any particular recruiting class)

Brand: Low (nothing to rehab in his personal brand)

Love for the University and College Life: Low (he is new to Virginia Tech)

On paper, Tuten, if he were to have a strong 2023 season, could face a decision similar to the one Evans did following the 2010 campaign. There are a lot of similarities between the two players, but some key differences in the broader environment, and drilling down on actual numbers will illuminate NIL’s role in all of this.

Let’s do some math!

I’m going to continue to consider the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the Go/Stay decision separately. These numbers will be tied loosely to the Bhayshul Tuten case study detailed above. For the purposes of this exercise, we will assume Tuten will be the first pick of the sixth round. I’ll be using the 2023 NFL contract numbers, but they will be similar to next year’s. For tax purposes, I am assuming Tuten will be single, childless, renting-not-owning, and living in Virginia, or a state with a similar tax burden.

Quantitative: Rookie contract

Four-year contract value (not guaranteed): $3,840,000, or $960,000 per year on average; Year 1 Cap: $804,576

Signing bonus (guaranteed): $218,304

Odds of making the opening day roster:

Year 1 - 70.2%

Year 2 - 57.5%

Year 3 - 35.3%

Year 4 - 20.9%

Average NFL career length: 3.3 years

Minimum Year 1 take home pay (after agent fee and taxes)

= Signing bonus - (taxes + agent fee)

= approximately $109,152

Maximum Year 1 take home pay

= Signing bonus take home + [Year 1 Cap * (1 - (tax rate + agent rate))]

= $109,152 + [$804,578 (1 - (0.45 + .03))]

= $109,152 + ($804,578 * 0.52)

= $109,152 + $418,381

= $527,533

Expected Year 1 take home pay

= Signing bonus take home + (Year 1 take home * odds of staying on an active roster for the full year)

= $109,152 + ($418,381 * 0.64)

= $109,152 + $267,764

= $376,916

Maximum take home pay for average career (3.3 years)

= Signing bonus take home + [3.3 (Avg Salary * (1-Tax and Agent Fee Rate))]

= $109,152 + [3.3 ($960,000 * 0.52)]

= $109,152 + $1,647,360

= $1,756,512

Lifetime value of a Bachelor’s degree = $900,000

Overall, if he were to go pro and get drafted early in the sixth round, Tuten would likely be looking at take home earnings north of $350,000 for the 2024-25 season. However, he would face multiple risks:

Anyone expected to get drafted on Day 3 could just as easily go undrafted

He is one major knee injury in the preseason away from netting out less than $200K, at which point he would be lucky to hang around on some team’s practice squad for a year or so following his recovery

If he were to flame out quickly, returning to Virginia Tech to complete his degree would likely cost around $100K (two years of out-of-state tuition and fees, unless he established residency in Virginia); if he did not complete his degree, he would be lucky to get a job that paid $20 per hour

Qualitative: The yearning to go pro

There are a lot of ways one can measure the qualitative factors. For simplicity’s sake, I’m going to use the following system:

Go Pro = -1 (the player’s situation indicates going pro is the best option)

No Opinion = 0 (the player’s situation does not point in either direction)

Stay in School = 1 (the player’s situation indicates returning for another year is the optimal decision)

You have probably already noticed that I left out perhaps the two most significant qualitative factors, namely the opportunity to achieve a lifelong dream (playing in the NFL) and the possibility of improving one’s draft position (by returning to school). I left them out because they both apply in every situation and they cancel one another out.

Preamble aside, let’s look at where Tuten stands on the qualitative factors:

Injury Risk = 0 (no injury history, but a bit on the small side for the NFL)

Legacy = -1 (unlikely to break any major records if he were to return)

Family = 0 (no public indications of their preference or special considerations)

Brotherhood = -1 (he transferred in and does not have a tight historical connection with anyone on the roster

Brand = -1 (no off the field issues to clean up, little upside if he were to return)

Love for the University and the College Life = -1 (I haven’t seen anything in the media about how his deep love for tubing on the New River in July and the fulfillment he gets each time he visits TOTS are worth more than money can buy)

Tuten’s overall qualitative score sums to -4, which clearly points to going pro. Given the neutral quantitative picture painted above, the qualitative score would likely be enough to send him packing for the NFL after the 2023 season were there no way to make money in college.

Enter NIL

Although, absent NIL, it would make sense for Bhayshul Tutem to go pro after the 2023 season, such a decision is far from a no brainer. Since Tuten would have one more year of eligibility remaining, and likely closer to two years of classes required to graduate, returning to Tech for his senior season would be worth around $1 million over the course of his life ($900K for the Bachelor’s degree and around $100K for cost of attendance covered by his scholarship). Unfortunately, those are both long-term benefits, while NFL earnings come in the present. In Tuten’s case, that would be the main reason to go.

That is where NIL comes in. Let’s suppose that he had an offer from Triumph NIL that would net him $75k per year after taxes, which seems reasonable based on a recent TSL article by Chris Coleman. Considering how many costs are covered by his scholarship and how little responsibility he has at this point in his life, he could live quite comfortably in Blacksburg while completing his degree and potentially raising his draft stock. Injury insurance, combined with a comparatively low maximum career take home pay for an average length career of $1.8m, means that the delta between the CI reimbursement and what he could have actually made in the NFL had there been no injury is comparatively small.

Looking back at Darren Evans, he too likely would have returned for the 2011 season had NIL existed at the time. He surely would have netted an NIL deal large enough to support his family. Yes, he would have split time with David Wilson, but don’t forget that Evans was the team’s leading rusher in 2010 while sharing a crowded backfield with Wilson, Ryan Williams, and the ever elusive Tyrod Taylor. And who knows, one more year might have been the difference in his getting drafted and enjoying a longer, and more lucrative, NFL career.

Regarding NIL’s potential macro impact, as the case studies in this article posit, I think the greatest impact will be on guys who receive a Day 3 draft grade. What we know about current NIL deals suggests that in many cases they will be a sufficient counter-incentive to keep the player in school for an extra year, if not two.

For Day 1 caliber players, declaring early is still a no brainer, and in most cases, the same will hold true for guys with a Day 2 grade. However, at schools with well-funded NIL collectives, we could see a lot more great-but-not-sure-thing-at-the-next-level players deciding to exhaust their eligibility before for leaving for the NFL.