How Close? How Far?

Since 2004, how close has Virginia Tech come to playing at a National Championship level? And how far has the program fallen?

With the Virginia Tech CFP, I generated a robust quantitative foundation for comparing various Virginia Tech teams from the last 20 years against one another. The playoff found that the 2004 team was the best Tech team of that era, and by a pretty comfortable margin. In this article, I will pull back and look at how each year’s Tech team compared to that year’s National Champion. Anything can happen when two teams play on an actual field, but through modelling and comparisons of advanced statistics, we can get a pretty good sense of what level National Champions play at, and how many VT teams have played at that level over the course of an entire season.

In addition to modelling expected outcomes, I will also examine ELO and Net EPA trends. By the end of the article, you should have a precise understanding of the heights to which Frank Beamer took the team and the depths to which it has fallen in recent years.

ELO Trend

ELO is one of my favorite methods of comparing one team to another because it is a straight forward metric. ELO rises when a given team defeats a quality opponent by a significant margin, and it falls when the opposite occurs. Since 2004, the ELO stats are as follows:

Only two National Champions, 2006 Florida and 2010 Auburn, finished with an ELO below 2000. In contrast, only two Virginia Tech teams have finished a season with an ELO over 2000: the 2004 and 2005 teams. The 2005 team had the highest ELO, 2091, but that was still 316 points less than Vince Young-led Texas, which won a thrilling title game over USC and finished with the highest ELO of any team in this era (higher than 2019 LSU and 2020 Alabama). That 300+ point ELO difference is similar to the difference between Virginia Tech and Ohio St. going into their 2014 matchup in Columbus (the one VT won 35-21).

In two years, 2004 and 2006, the ELO difference between VT and the National Champion was less than 100 points. On five occasions (2013, 2018, 2020, 2021, and 2022) the Hokies finished with an ELO rating more than 800 points less than the National Champion, including a max difference of -982 points in 2022.

Overall, the trends are as follows:

While National Champion ELOs have increased slightly in the last 20 years, Virginia Tech’s has declined by about 700 points, or approximately one-third. Winning a game against a team with an ELO 300 points higher is a major upset. Defeating a team with an ELO 900 points higher gets into Miracle on Ice territory.

EPA

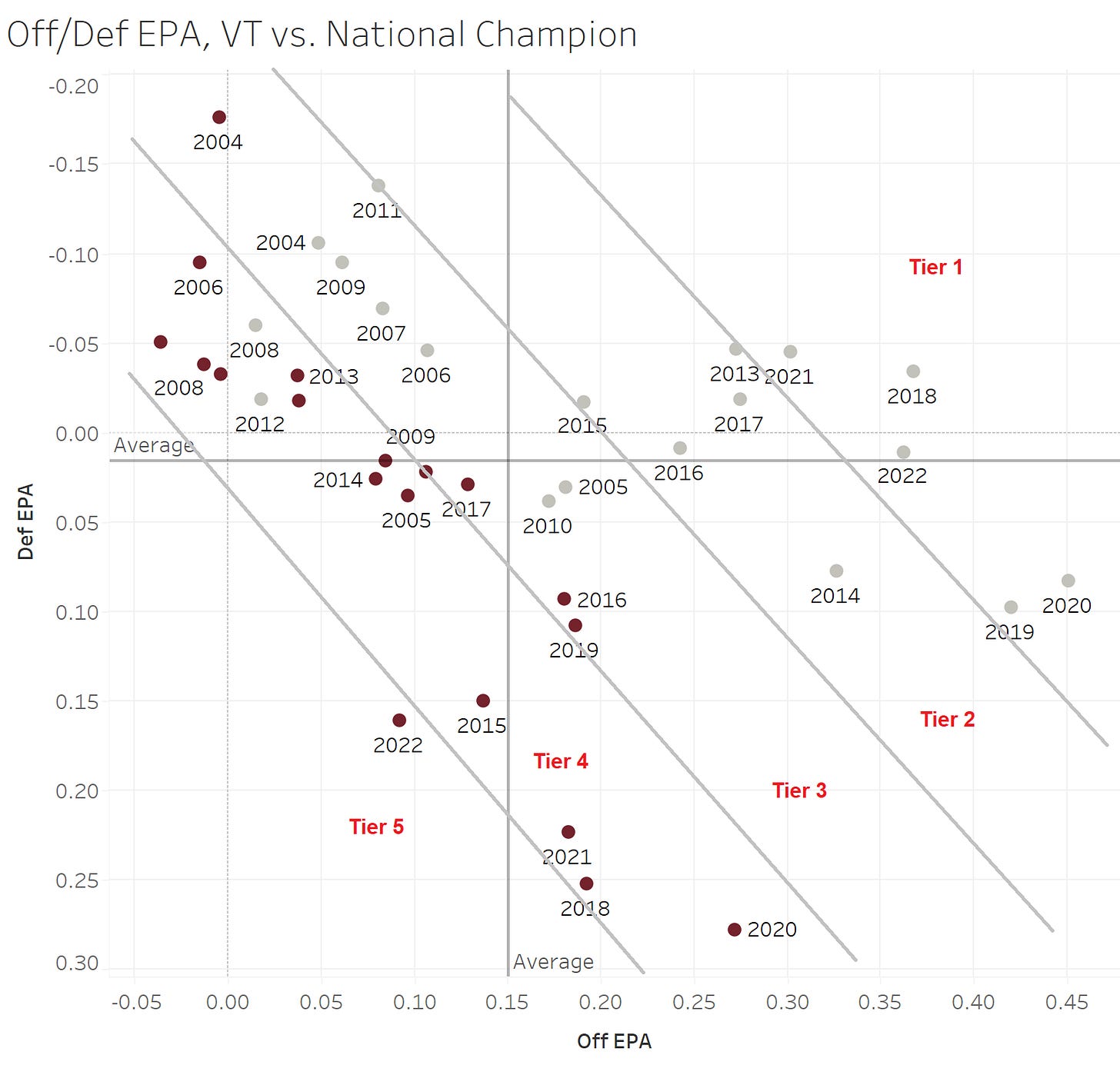

Another way of comparing Virginia Tech to the eventual National Champion is to look at offensive, defensive, and net expected points added (EPA). The proliferation of explosive offenses is reflected in the rise in Offensive EPA and decline in Defensive EPA. However, the net figure, as well as the interplay between both sides of the ball is still revealing. As this scatter plot shows, only the 2004 Hokies are really in the conversation with a decent segment of the National Champions. Some of the best Fuente era teams also sneak into Tier 3, but just barely. Only two National Champions fell into Tier 4 (2008 Florida and 2012 Alabama).

While ELO is a great indicator of strength over the course of a season, it is less informative when it comes to postseason and playoff games. As we have seen in recent years, defense still wins championships, but only if you have an offense that can move the ball and score. That assertion is clearly demonstrated in the above scatter plot, which shows the difference between the Hokies and the National Champs on both sides of the ball, and especially highlights Virginia Tech’s offensive deficiencies through the years.

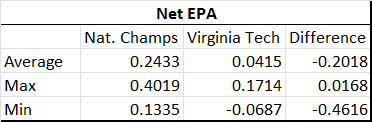

Turning to Net EPA, the story is even more bleak. Only one Tech team (the 2004 Hokies) had a better Net EPA than the National Champions. In most years, VT trailed by a significant margin.

The Net EPA Difference trend mirrors what we see in ELO ratings, only to a greater degree. The Hokies have gone from slightly favorable in their comparison to the National Champions to distinctly unfavorable in 19 years. Half of the difference has come since 2018, when the VT program took a steep nosedive.

Expected Outcomes

The third way I examined the difference between Virginia Tech and the National Championship team from each year is by running the teams through the model I used for the VT CFP. I have said on numerous occasions that one of the outputs of the model is a score prediction. However, it would be more accurate to call this output an expected result. A score prediction would factor in qualitative data like motivation, matchup (some teams give others fits year after year regardless of the relative strength and talent of each) as well as data points that are not currently quantifiable, such as injuries (not just players who are unable to play but also those who are playing hurt).

The aggregated findings from modelled expected outcomes since 2004 are:

Closest Game: 2004 USC 18 vs. VT 17

Biggest Blowout: 2018 Clemson 61 vs. VT 0

Average Game: National Champion 37 vs. VT 13

Game with the Most Points Scored by Virginia Tech: 2019 LSU 43 vs. VT 31

Shutouts by the National Champion: 3 (2018 Clemson, 2021 Georgia, 2022 Georgia)

One-Score Games: 2004 (USC wins 18-17), 2006 (Florida wins 22-19), and 2007 (LSU wins 29-21)

35+ Point Margin: 2008 (Florida wins 42-6), 2013 (Florida St. wins 48-10), 2018 (Clemson wins 61-0), 2021 (Georgia wins 45-0), and 2022 (Georgia wins 40-0)

According to the model, no Virginia Tech team would be expected to beat the National Champion from that year. The closest the Hokies would come is the 2004 team playing a rematch against USC. On average, the Hokies lose each matchup by a convincing 24 points, with the gap growing significantly over time. Somewhat surprisingly, the 2007 Hokies would be expected to join the 2004 team in playing a close rematch from an earlier game against the eventual National Champion. In both cases, Tech was stronger at the end of the season because the Hokies were giving significant playing time to stud freshmen (Eddie Royal, Josh Morgan, and Xavier Adibi in 2004 and Tyrod Taylor in 2007) that had sat earlier in the year in favor of middling veterans or due to injury.

While there are peaks and valleys in expected outcomes, the trend in point differential is unmistakably negative.

A few more tidbits about specific expected outcomes:

If it could, the model would have predicted 2022 Georgia holding Virginia Tech to -8 points. The only other team that would be limited to negative points if it could would be the 2018 Hokies (-1).

The 2019 team would be expected to fare rather well against LSU, a team that featured perhaps the greatest offense of all-time. While the model looks at the totality of each team’s games, I’ll go ahead and qualify that those 2019 Hokies were a decidedly different (undefeated!) team when they started both Hendon Hooker and Caleb Farley. Take at least one of them away, and that team was looking at almost certain defeat (albeit, Duke aside, in a close game).

The 2005 team, which in early November of that year was ranked third in both polls behind USC and Texas, would be expected to lose to the Longhorns 42-13 in a hypothetical postseason game. Given how that Tech team melted down on big stages against lesser Miami (27-7) and FSU (27-22) teams, a 29-point loss to Vince Young & Crew feels about right.

The Takeaway

The 2004 Hokies finished the year 10-3 overall, 7-1 in the ACC, and #10 in the final AP and Coaches polls. However, that team played at a near National Champion level, so much so that we would expect those Hokies to lose to USC in a hypothetical title game by a single point. That 2004 team, when considering the three metrics presented in this article, would be around the 25th percentile of National Champions since 2004 had they in fact won the title.

From 2005 to 2011, the remainder of the 10-win streak seasons, the expected outcome of matchups with the National Champion yielded an average defeat of 17 points. So, while it felt like Tech was in the highest tier of college football teams during that stretch, the Hokies were really a step or two down from the very best teams.

Things got worse from there. From 2012 to 2022, the expected margin of defeat extended to 31 points, with only two games (against 2016 Clemson and 2019 LSU) expected to be decided by less than two touchdowns.

So, clearly, the difference between how well the Hokies have played in recent years and how well National Champion teams have played has increased. Both the eye test and advanced stats tell us that Tech has gotten worse over the years. But what about the National Champions? Have they gotten better or worse over time?

Next week I will compare the 2004 Hokies to all the title winning teams. Yes, individual matchups matter, but by holding one Hokie team constant, in this case the best one, we should be able to uncover any trends regarding the strengthening or weakening of National Champions since 2004. At that point, we will have a clear and quantified answer as to how far Brent Pry and his staff have to raise the level of play by his team to have a legitimate shot at winning a National Championship.